From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- For other uses, see Wolf (disambiguation), Gray Wolves (disambiguation), or Timber Wolf (comics).

The gray wolf (Canis lupus), also known as the timber wolf or, simply, wolf, is a mammal of the order Carnivora. The gray wolf is the largest member of the family Canidae and also the most well known of wolves. Its shoulder height ranges from 0.6 to 0.9 meters (26–36 inches) and its weight typically varies between 32 and 62 kilograms (70–135 pounds). As evidenced by studies of DNA sequencing and genetic drift the gray wolf shares a common ancestry with the domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris).[2]

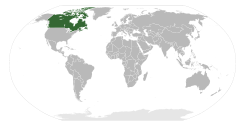

Though once abundant over much of North America and Eurasia, the gray wolf inhabits a very small portion of its former range because of widespread destruction of its habitat; in some regions it is endangered or threatened. Considered as a whole, however, the gray wolf is regarded as of least concern for extinction according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Wolves are still hunted in many areas for sport or as perceived threats to livestock. Kazakhstan is currently thought to have the largest wolf population of any nation; it has as many as 90,000, versus some 60,000 for Canada.[3]

Gray wolves play an important role as apex predators in the ecosystems they typically occupy. Gray wolves have been known to thrive in temperate forests, deserts, mountains, tundra, taiga, and grasslands; this diversity reflects the wolf's adaptability as a species.

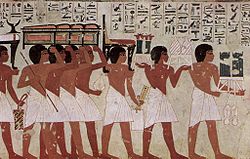

Wolves feature in folklore and mythology of cultures ancient to modern across the northern hemisphere; from the Norse legend of the giant Fenrir to more sympathetic depictions in Central Asia and the suckling of Romulus and Remus in the foundation of Rome. More familiar still are the fairy tales where the wolf appears as a villain such as Little Red Riding Hood and the Three Little Pigs. Wolf legends have also given rise to the popular horror figure of the werewolf.

[edit] Behavior and physiology

[edit] Ecophysiology

Wolf weight and size can vary greatly worldwide, tending to increase proportionally with latitude as predicted by Bergmann's Rule. In general, height varies from 0.6 to 0.95 meters (26–38 inches) at the shoulder and weight ranges from 32 to 62 kilograms (70–135 pounds), which together make the gray wolf the largest of all wild canids.[4] Although rarely encountered, extreme specimens of more than 77 kg (170 lb) have been recorded in Alaska and Canada.[5] The heaviest wild wolf on record, killed in Alaska in 1939, was 80 kg (175 lb).[6] The smallest wolves come from the Arabian Wolf subspecies, the females of which may weigh as little as 10 kg (22 lb) at maturity. Females in any given wolf population typically weigh about 20% less than their male counterparts.[7] Wolves can measure anywhere from 1.3 to 2 meters (4.5–6.5 feet) from nose to the tip of the tail, which itself accounts for approximately one quarter of overall body length.[8]

Wolves usually have blended pelages.

Wolves are built for stamina, possessing features ideal for long-distance travel. Their narrow chests and powerful backs and legs facilitate efficient locomotion. They are capable of covering several miles trotting at about a pace of 10 km/h (6 mph), and have been known to reach speeds approaching 65 km/h (40 mph) during a chase.[9] While thus sprinting, wolves can cover up to 5 meters (16 ft) per bound.[10]

Wolf paws are able to tread easily on a wide variety of terrains, especially snow. There is a slight webbing between each toe, which allows them to move over snow more easily than comparatively hampered prey. Wolves are digitigrade, which, with the relative largeness of their feet, helps them to distribute their weight well on snowy surfaces. The front paws are larger than the hind paws, and have a fifth digit, the dewclaw, that is absent on hind paws.[11] Bristled hairs and blunt claws enhance grip on slippery surfaces, and special blood vessels keep paw pads from freezing.[12] Scent glands located between a wolf's toes leave trace chemical markers behind, helping the wolf to effectively navigate over large expanses while concurrently keeping others informed of its whereabouts.[12] Unlike dogs and coyotes, wolves lack sweat glands on their paw pads. This trait is also present in Eastern Canadian Coyotes which have been shown to have recent wolf ancestry.[13] Wolves in Israel are unique due to the middle two toes of their paws being fused, a trait originally thought to be unique to the African Wild Dog.[14]

Wolves molt in late spring or early summer.

Wolves have bulky coats consisting of two layers. The first layer is made up of tough guard hairs designed to repel water and dirt. The second is a dense, water-resistant undercoat that insulates. The undercoat is shed in the form of large tufts of fur in late spring or early summer (with yearly variations). A wolf will often rub against objects such as rocks and branches to encourage the loose fur to fall out. The undercoat is usually gray regardless of the outer coat's appearance. Wolves have distinct winter and summer pelages that alternate in spring and autumn. Females tend to keep their winter coats further into the spring than males. North American wolves typically have longer, silkier fur than their Eurasian counterparts.[15]

Fur coloration varies greatly, running from gray to gray-brown, all the way through the canine spectrum of white, red, brown, and black. These colors tend to mix in many populations to form predominantly blended individuals, though it is certainly not uncommon for an individual or an entire population to be entirely one color (usually all black or all white). A multicolor coat characteristically lacks any clear pattern other than it tends to be lighter on the animal's underside. Fur color sometimes corresponds with a given wolf population's environment; for example, all-white wolves are much more common in areas with perennial snow cover. Aging wolves acquire a grayish tint in their coats.

It is often thought that the coloration of the wolf's pelage serves as a functional form of camouflage. This may not be entirely correct, as some scientists have concluded that the blended colors have more to do with emphasizing certain gestures during interaction.[16]

At birth, wolf pups tend to have darker fur and blue irises that will change to a yellow-gold or orange color when the pups are between 8 and 16 weeks old.[17] Though extremely unusual, it is possible for an adult wolf to retain its blue-colored irises.[18]

Adolescent wolf with golden-yellow eyes.

Wolves' long, powerful muzzles help distinguish them from other canids, particularly coyotes and golden jackals, which have more narrow, pointed muzzles. Wolves differ from domestic dogs in a more varied nature. Anatomically, wolves have smaller orbital angles than dogs (>53 degrees for dogs compared with <45 degrees for wolves) and a comparatively larger brain capacity.[19] Larger paw size, yellow eyes, longer legs, and bigger teeth further distinguish adult wolves from other canids, especially dogs. Also, precaudal glands at the base of the tail are present in wolves but not in dogs.

Wolves and most larger dogs share identical dentition. The maxilla has six incisors, two canines, eight premolars, and four molars. The mandible has six incisors, two canines, eight premolars, and six molars.[20] The fourth upper premolars and first lower molars constitute the carnassial teeth, which are essential tools for shearing flesh. The long canine teeth are also important, in that they are designed to hold and subdue the prey. Capable of delivering up to 10,000 kPa (1450 lbf/in²) of pressure, a wolf's teeth are its main weapons as well as its primary tools.[6] Therefore, any injury to the jaw line or teeth could devastate a wolf, dooming it to starvation or incapacity.

[edit] Reproductive physiology and life cycle

Usually, the instinct to reproduce drives young wolves away from their birth packs, leading them to seek out mates and territories of their own. Dispersals occur at all times during the year, typically involving wolves that have reached sexual maturity prior to the previous breeding season. It takes two such dispersals from two separate packs for a new breeding pair to be formed, for dispersing wolves from the same maternal pack tend not to mate.[21] Once two dispersing wolves meet and begin traveling together, they immediately begin the process of seeking out territory, preferably in time for the next mating season. The bond that forms between these wolves often lasts until one of them dies.[22]

Generally, mating occurs between January and April — the higher the latitude, the later it occurs.[22] A pack usually produces a single litter unless the alpha male mates with one or more subordinate females. During the mating season, breeding wolves become very affectionate with one another in anticipation of the female's ovulation cycle. The pack tension rises as each mature wolf feels urged to mate. During this time, in fact, the alpha male and alpha female may be forced to prevent other wolves from mating with one another.[21] Under normal circumstances, a pack can only support one litter per year, so this dominance behavior is beneficial in the long run.

When the alpha female goes into estrus (which occurs once per year and lasts 5–14 days),[23] she and her mate will spend an extended time in seclusion. Pheromones in the female's urine and the swelling of her vulva make known to the male that the female is in heat. The female is unreceptive for the first few days of estrus, during which time she sheds the lining of her uterus; but when she begins ovulating again, the two wolves mate.

The male wolf will mount the female firmly from behind. After achieving coitus, the two form a copulatory tie once the male's bulbus glandis—an erectile tissue located near the base of the canine penis—swells and the female's vaginal muscles tighten. Ejaculation is induced by the thrusting of the male's pelvis and the undulation of the female's cervix. The two become physically inseparable for anywhere from 10 to 30 minutes, during which the male will ejaculate multiple times.[24][25] After the initial ejaculation, the male may lift one of his legs over the female such that they are standing end-to-end; this is believed to be a defensive measure.[25] The mating ritual is repeated many times throughout the female's brief ovulation period, which occurs once per year per female—unlike female dogs, whose estrus usually occurs twice per year.

A wolf resting at the entrance to its den; also note how its coloration blends in with the environment.

The gestation period lasts between 60 and 63 days. The pups, at a weight of 0.5 kg (1 lb), are born blind, deaf, and completely dependent on their mother.[22][4] There can be anywhere from 1 to 14 pups per litter, with the average litter size being about 4 to 6.[26] Pups reside in the den and stay there for no longer than two months. The den is usually on high ground near an open water source, and has an open "room" at the end of an underground or hillside tunnel that can be up to a few meters long.[12] During this time, the pups will become more independent, and will eventually begin to explore the area immediately outside the den before gradually roaming up to a mile away from it at around 5 weeks of age. They begin eating regurgitated foods after 2 weeks — by which time their milk teeth have emerged — and are fully weaned by 10 weeks. During the first weeks of development, the mother usually stays with her litter alone, but eventually most members of the pack will contribute to the rearing of the pups in some way.[22]

After two months, the restless pups will be moved to a rendezvous site, where they can stay safely while most of the adults go out to hunt. One or two adults stay behind to ensure the safety of the pups. After a few more weeks, the pups are permitted to join the adults if they are able, and will receive priority on anything killed, their low ranks notwithstanding. Letting the pups fight for eating privileges results in a secondary ranking being formed among them, and allows them to practice the dominance/submission rituals that will be essential to their future survival in pack life.[22] During hunts, the pups remain ardent observers until they reach about 8 months of age, by which time they are large enough to participate actively.

Wolves typically reach sexual maturity after two or three years, at which point many of them will be compelled to leave their birth packs and seek out mates and territories of their own.[22][27] Wolves that reach maturity generally live 6 to 8 years in the wild, although in captivity they can live to twice that age.[26] High mortality rates give them a low overall life expectancy. Pups die when food is scarce; they can also fall prey to predators such as bears, or, less often, coyotes, foxes, or other wolves. The most significant causes of mortality for grown wolves are hunting and poaching, car accidents, and wounds inflicted while hunting prey. Although adult wolves may be killed by other predators occasionally, rival wolf packs are often their most dangerous non-human enemy. A study on wolf mortality concluded that 14–65% of wolf deaths were inflicted by other wolves.[28]

Wolves are susceptible to the same infections that affect domestic dogs, such as mange, heartworm, rabies, parvovirus and canine distemper. Epidemics of these can drastically reduce wolf populations in a given area. Wolves are reported to carry over 50 types of parasites, including echinococci, cysticercocci, coeruni (all of which can attach humans) and the trichinellidae family.[29]

[edit] Behavior

[edit] Body language

- See also: Dog communication

This facial expression is defensive and gives warning to other wolves to be cautious.

This facial expression shows fear.

This wolf's submissive posture, wagging tail and horizontal ears show a friendly greeting.

Wolves can communicate visually through a wide variety of expressions and moods ranging from subtle signals, such as a slight shift in weight, to more obvious ones, such as rolling on their backs to indicate complete submission.[30]

- Dominance – A dominant wolf stands stiff legged and tall. The ears are erect and forward, and the hackles bristle slightly. Often the tail is held vertically and curled toward the back. This display asserts the wolf's rank to others in the pack. A dominant wolf may stare at a submissive one, pin it to the ground, "ride up" on its shoulders, or even stand on its hind legs.

- Submission (active) – During active submission, the entire body is lowered, and the lips and ears are drawn back. Sometimes active submission is accompanied by muzzle licking, or the rapid thrusting out of the tongue and lowering of the hindquarters. The tail is placed down, or halfway or fully between the legs, and the muzzle often points up to the more dominant animal. The back may be partly arched as the submissive wolf humbles itself to its superior; a more arched back and more tucked tail indicate a greater level of submission.

- Submission (passive) – Passive submission is more intense than active submission. The wolf rolls on its back and exposes its vulnerable throat and underside. The paws are drawn into the body. This posture is often accompanied by whimpering.

- Anger – An angry wolf's ears are erect, and its fur bristles. The lips may curl up or pull back, and the incisors are displayed. The wolf may also arch its back, lash out, or snarl.

- Fear – A frightened wolf attempts to make itself look small and less conspicuous; the ears flatten against the head, and the tail may be tucked between the legs, as with a submissive wolf. There may also be whimpering or barks of fear, and the wolf may arch its back.

- Defensive – A defensive wolf flattens its ears against its head.

- Aggression – An aggressive wolf snarls and its fur bristles. The wolf may crouch, ready to attack if necessary.

- Suspicion – Pulling back of the ears shows a wolf is suspicious. The wolf also narrows its eyes. The tail of a wolf that senses danger points straight out, parallel to the ground.

- Relaxation – A relaxed wolf's tail points straight down, and the wolf may rest sphinx-like or on its side. The wolf may also wag its tail. The further down the tail droops, the more relaxed the wolf is.

- Tension – An aroused wolf's tail points straight out, and the wolf may crouch as if ready to spring.

- Happiness – As dogs do, a wolf may wag its tail if in a joyful mood. The tongue may loll out of the mouth.

- Hunting – A wolf that is hunting is tensed, and therefore the tail is horizontal and straight.

- Playfulness – A playful wolf holds its tail high and wags it. The wolf may frolic and dance around, or bow by placing the front of its body down to the ground, while holding the rear high, sometimes wagged. This resembles the playful behavior of domestic dogs.

[edit] Howling

Howling helps pack members keep in touch, allowing them to communicate effectively in thickly forested areas or over great distances. Howling also helps to call pack members to a specific location. Howling can also serve as a declaration of territory, as shown in a dominant wolf's tendency to respond to a human imitation of a "rival" wolf in an area the wolf considers its own. This behavior is stimulated when a pack has something to protect, such as a fresh kill. As a rule of thumb, large packs will more readily draw attention to themselves than will smaller packs. Adjacent packs may respond to each others' howls, which can mean trouble for the smaller of the two. Wolves therefore tend to howl with great care.[31]

Wolves will also howl for communal reasons. Some scientists speculate that such group sessions strengthen the wolves' social bonds and camaraderie—similar to community singing among humans.[31] During such choral sessions, wolves will howl at different tones and varying pitches, making it difficult to estimate the number of wolves involved. This confusion of numbers makes a listening rival pack wary of what action to take. For example, confrontation could be disastrous if the rival pack gravely underestimates the howling pack's numbers. A wolf's howl may be heard from up to ten miles away, depending on weather conditions.

Observations of wolf packs suggest that howling occurs most often during the twilight hours, preceding the adults' departure to the hunt and following their return. Studies also show that wolves howl more frequently during the breeding season and subsequent rearing process. The pups themselves begin howling soon after emerging from their dens and can be provoked into howling sessions easily over the following two months. Such indiscriminate howling usually is intended for communication, and does not harm the wolf so early in its life.[31] Howling becomes less indiscriminate as wolves learn to distinguish howling pack members from rival wolves.

The Middle Eastern and South-East Asiatic wolf subspecies are unusual as they are not known to howl.[16][32]

[edit] Other vocalizations

Growling, while teeth are bared, is the most visual and effective warning wolves use. Wolf growls have a distinct, deep, bass-like quality, and are often used to threaten rivals, though not necessarily to defend themselves. Wolves also growl at other wolves while being aggressively dominant. Wolves bark when nervous or when they want to warn other wolves of danger. Wolves bark very discreetly, and will not generally bark loudly or repeatedly as dogs do; rather, they use a low-key, breathy "whuf" sound to immediately get attention from other wolves. Wolves also "bark-howl" by adding a brief howl to the end of a bark. Wolves bark-howl for the same reasons they normally bark. Generally, pups bark and bark-howl much more frequently than adults, using these vocalizations to cry for attention, care, or food. A lesser known sound is the rally. Wolves will gather as a group and, amidst much tail-wagging and muzzle licking, emit a high-pitched wailing noise interspersed with something similar (but not the same as) a bark. Rallying is often a display of submission to an alpha by the other wolves.[33] Wolves also whimper, usually when submitting to other wolves. Wolf pups whimper when they need a reassurance of security from their parents or other wolves.

[edit] Scent marking

Wolves scent-roll to bring scents back to the pack.

Wolves, like other canines, use scent marking to lay claim to anything—from territory to fresh kills.[34] Alpha wolves scent mark the most often, with males doing so more than females. The most widely used scent marker is urine. Male and female alpha wolves urine-mark objects with a raised-leg stance (all other pack members squat) to enforce rank and territory. They also use marks to identify food caches and to claim kills on behalf of the pack. Defecation markers are used for the same purpose as urine marks, and serve as a more visual warning, as well.[34] Defecation markers are particularly useful for navigation, keeping the pack from traversing the same terrain too often and also allowing each wolf to be aware of the whereabouts of its pack members. Above all, though, scent marking is used to inform other wolves and packs that a certain territory is occupied, and that they should therefore tread cautiously.

Wolves have scent glands all over their bodies, including at the base of the tail, between toes, and in the eyes, genitalia, and skin.[34] Pheromones secreted by these glands identify each individual wolf. A dominant wolf will "rub" its body against subordinate wolves to mark such wolves as being members of a particular pack. Wolves may also "paw" dirt to release pheromones instead of urine marking.[35]

Wolves' heavy reliance on odoriferous signals testifies greatly to their olfactory capabilities. Wolves can detect virtually any scent, including marks, from great distances, and can distinguish among them as well or better than humans can distinguish other humans visually.[citation needed]

[edit] Social structure

A pack of

Italian wolves at the Parc des Loups.

Wolves function as social predators and hunt in packs organized according to strict, rank-oriented social hierarchies.[22] It was originally believed that this comparatively high level of social organization was related to hunting success, and while this still may be true to a certain extent, emerging theories suggest that the pack has less to do with hunting and more to do with reproductive success.

The pack is led by the two individuals that sit atop the social hierarchy: the alpha male and the alpha female. The alpha pair has the greatest amount of social freedom compared to the rest of the pack. Although they are not "leaders" in the human sense of the term, they help to resolve any disputes within the pack, have the greatest amount of control over resources (such as food), and, most importantly, they help keep the pack cohesive and functional.

While most alpha pairs are monogamous, there are exceptions.[36] An alpha animal may preferentially mate with a lower-ranking animal, especially if the other alpha is closely related (a brother or sister, for example). The death of one alpha does not affect the status of the other alpha, who will quickly take another mate.[22]

Usually, only the alpha pair is able to rear a litter of pups successfully. Other wolves in a pack may breed, but when resources are limited, time, devotion, and preference will be given to the alpha pair's litter. Therefore, non-alpha parents of other litters within a single pack may lack the means to raise their pups to maturity of their own accord. All wolves in a pack assist in raising wolf pups. Some mature individuals choosing not to disperse may stay in their original packs so as to reinforce it and help rear more pups.

The size of the pack may change over time and is controlled by several factors, including habitat, personalities of individual wolves within a pack, and food supply. Packs can contain between 2 and 20 wolves, though 8 is a more typical size.[37] New packs are formed when a wolf leaves its birth pack, finds a mate, and claims a territory. Lone wolves searching for other individuals can travel very long distances seeking out suitable territories. Dispersing individuals must avoid the territories of other wolves because intruders on occupied territories are chased away or killed. It is taboo for one wolf to travel into another wolf's territory unless invited. Most dogs, except perhaps large, specially bred attack dogs, do not stand much of a chance against a pack of wolves protecting its territory from an intrusion.

Wolves acting unusually within the pack, such as epileptic pups or thrashing adults crippled by a trap or a gunshot, are usually killed by other members of their own pack.[16]

[edit] Hierarchy

The hierarchy, led by the alpha male and female, affects all activity in the pack to some extent. In most larger packs there are two separate hierarchies in addition to an overbearing one: the first consists of the males, led by the alpha male, and the other consists of the females, led by the alpha female.[12] In this situation, the alpha male was originally assumed to be the "top" alpha, but biologists have since concluded that alpha females can and do take control over entire packs.[citation needed] The male and female hierarchies are interdependent and are maintained constantly by aggressive and elaborate displays of dominance and submission.

After the alpha pair, there may also, especially in larger packs, be a beta wolf or wolves, a "second-in-command" to the alphas. Betas typically assume a more prominent role in assisting with the upbringing of the alpha pair's litter, often serving as surrogate mothers or fathers while the alpha pair is away. Beta wolves are the most likely to challenge their superiors for the role of the alpha, though some betas seem content with being second, and will sometimes even let lower ranking wolves leapfrog them for the position of alpha should circumstances necessitate such a happening, such as the death of the alpha. More ambitious beta wolves, however, will only wait so long before contending for alpha position unless they choose to disperse and create their own pack instead.

Loss of rank can happen gradually or suddenly. An older wolf may simply choose to give way when a motivated challenger presents itself, yielding its position without bloodshed. On the other hand, the challenged individual may choose to fight back with varying degrees of intensity. While the majority of wolf aggression is ritualized and non-injurious, a high-stakes fight can easily result in injury for either or both parties. The loser of such a confrontation is frequently chased away from the pack or, rarely, may be killed as other aggressive wolves contribute to the insurgency. These types of confrontations are more common during the mating season. Though rare, deaths can and will occur, as the average alpha male wolf kills two to four wolves in his lifetime.[38]

Rank order within a pack is established and maintained through a series of ritualized fights and posturing best described as "ritual bluffing". Wolves prefer psychological warfare to physical confrontations, meaning that high-ranking status is based more on personality or attitude than on size or physical strength. Rank, who holds it, and how it is enforced varies widely between packs and between individual animals. In large packs full of easygoing wolves or in a group of juvenile wolves, rank order may shift almost constantly, or even be circular (for instance, animal A dominates animal B, who dominates animal C, who dominates animal A).

In a more typical pack, only one wolf will assume the role of the omega: the lowest-ranking member of a pack.[34] Omegas receive the most aggression from the rest of the pack, and may be subjected to different forms of truculence at any time—anything from constant dominance from other pack members to inimical, physical harassment. Although this arrangement may seem objectionable, the nature of pack dynamics demands that one wolf be at the bottom of the ranking order, and submissive individuals are better suited for constant displays of active and passive submission than they are for living alone. Any form of camaraderie is preferable to solitude and, indeed, submissive wolves tend to choose low rank over potential starvation. Despite the aggression to which they are often subjected, omega wolves have also been observed to be among the most playful wolves in the pack, often enticing all of the members in a pack into chasing games and other forms of play. In general, omega wolves exist to help relieve pack tension, be it as punching bags or as pack jesters.

[edit] Hunting and diet

Packs of wolves cooperatively hunt any large herbivores in their range. Pack hunting revolves around the chase, as wolves are able to run for long periods before relenting. It takes careful cooperation for a pack to take down large prey, and the rate of success for such chase is very low. Wolves, in the interest of saving energy, will only chase one potential prey for the first thousand or so meters before giving up and trying at a different time against a different prey.[39] Therefore, like most other pack species, wolves must hunt continually to sustain themselves. Solitary wolves depend more on smaller animals, which they capture by pouncing and pinning with their front paws. This technique is also common among other canids such as foxes and coyotes.

Wolves' diets include, but are not limited to, deer, caribou, moose, yak, and other large ungulates. The American Bison is probably the heaviest animal wolves prey on — bison weighing more than a ton having been taken down by a pack. They also prey on rodents and other small animals in a limited manner, as a typical adult wolf requires a minimum of 1.1 kg (2.5 lb) of food each day for sustenance, and approximately 2.2 kg (5lb) to reproduce successfully.[26] Wolves rarely eat each day, but compensate by eating up to 10 kg (22 lb) at a time.[26]

An

American Bison standing its ground, thereby increasing its chance for survival.

When pursuing large prey, wolves generally attack from all angles, targeting the necks and sides of their prey. Wolf packs test large populations of prey species by initiating a chase, targeting less-fit prey. Such animals typically include the elderly, diseased, and young.[27] Healthy animals may also succumb through circumstance. However, most healthy, fit individuals will not run from wolves and will instead choose to stand their ground. This defensive technique increases the possibility of injury to the preying wolves. The wolves, not willing to risk injury, are more likely to yield when encountered with such a bold individual. Instead, they will try to target weaker prey members that are easier and safer to hunt. Wolves are generally inefficient at killing large healthy prey, with success rates as low as 20% which is due, in part, to the large size and defensive capabilities of their prey.[40]

Like many other keystone predators, wolves are sensitive to fluctuations in the abundance of prey. They are likely to have minor changes in their populations as the abundance of their primary prey species gradually rises and drops over long periods of time. This balance between wolves and their prey prevents the mass starvation of both predator and prey.

[edit] Surplus killing

Surplus killing is defined as the killing of several prey animals too numerous to eat at one sitting. During a surplus-kill, a predator's killing instinct is continually sparked off by the stimuli of so many prey animals unable to escape, so that the predator cannot stop killing. An instance of surplus killing by wolves was witnessed in Canada's Northwest Territories by researchers coming across 34 neonatal caribou calves, scattered over three square kilometres. The wolves had eaten only a few parts from half the calves and not touched the rest. Wolves sometimes only eat a part of their surplus-killed prey, like the tail or the internal organs.

However, conditions in nature which favour surplus killing are unusual. Consequently surplus killing in the wild is rare, though fairly common in domestic situations in which the prey animals are usually confined and unable to escape the attackers. [41]

[edit] Taxonomy

The gray wolf is a member of the genus Canis, which comprises between 7 and 10 species. It is one of six species termed 'wolf', the others being the Red Wolf (Canis rufus), the Indian Wolf (Canis indica), the Himalayan wolf (Canis himalayaensis), the Eastern Canadian Wolf (Canis lycaon) and the Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis).

With respect to common names, spelling differences result in the alternative spelling grey wolf. As the first-named and most widespread of species termed "wolf", gray wolves are often simply referred to as wolves. It was one of the many species originally described by Carolus Linnaeus in his eighteenth-century work, Systema Naturae, and it still bears its original classification, Canis lupus.[42] The binomial name is derived from the Latin Canis, meaning "dog", and lupus, "wolf".[43]

Desert dwelling grey wolf subspecies, such as this Arabian wolf, tend to be smaller than their more northern cousins.

Classifying gray wolf subspecies can be challenging. Although scientists have proposed a host of subspecies, wolf taxonomy at this level remains controversial.[44] Indeed, only a single wolf species may exist. Taxonomic modification will likely continue for years to come.

Current theories propose that the gray wolf first evolved in Eurasia during the early Pleistocene. The rate of changes observed in DNA sequence date the South-East Asiatic lineage to about 800,000 years, as opposed to the American and European lineages which stretch back only 150,000.[45] The gray wolf then migrated into North America from the Old World, probably via the Bering land bridge (that once joined Alaska and Siberia), around 400,000 years ago. The gray wolf then coexisted with the Dire Wolf (Canis dirus), a Canid species that was larger and heavier than the gray wolf and appeared in South America over 700,000 years ago and whose origin is still speculated. The Dire Wolf ranged from southern Canada to South America until about 8,000 years ago when climate changes are thought to have caused it to become extinct. After that the gray wolf is thought to have become the prime canine predator in North America.

[edit] Subspecies

At one point, up to 50 gray wolf subspecies were recognized. Though no true consensus has been reached, this list can be condensed to 13–15 general extant subspecies. Modern classifications take into account the DNA, anatomy, distribution, and migration of various wolf colonies.

| Subspecies |

Classification |

Status |

Historic Range (see map) |

| Arabian Wolf |

Canis lupus Arabs |

Critically endangered, declining |

Southern Israel, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman |

| A very small subspecies. Typically blended brown or completely brown with a thin coat. Hunted regularly as a nuisance animal, though rarely encountered. |

| Arctic Wolf |

Canis lupus arctos |

Stable |

Canadian Arctic, Greenland |

| An average-sized subspecies. Almost exclusively white or creamy white with a thick coat. Hunted legally, though rarely encountered. |

| Caspian Sea Wolf |

Canis lupus cubanensis |

Endangered, declining |

Between the Caspian and Black seas |

| A smaller subspecies. Hunted as a nuisance animal. |

| Dingo |

Canis lupus dingo |

Vulnerable

(pure breed) |

Australia & southeast Asia |

| Hunted as a nuisance animal. Pure breed declining from interbreeding with the Domestic Dog. |

| Domestic Dog |

Canis lupus familiaris |

Stable |

Worldwide |

| Typically, a smaller subspecies, with 20% smaller brains, less powerful immune system, and less developed sense of smell. Maintained as pets, although some small feral populations do exist. Raised for their meat in some parts of the world. |

| Eastern Timber Wolf |

Canis lupus lycaon |

At risk |

Southeastern Canada, Eastern United States |

| A larger subspecies. Full canine color spectrum represented, though blended pelages predominate. First subspecies to be recognized in North America. Hunted legally in parts of Canada. |

| Egyptian Wolf |

Canis lupus lupaster |

Critically endangered, unknown |

Far Northern Africa |

| A smaller subspecies. Usually a grizzled or tinged gray or brown. Lanky. Very rarely encountered. |

| Eurasian Wolf |

Canis lupus lupus |

Stable |

Western Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, China, Mongolia, Himalaya Mountains |

| An average to large-sized subspecies. Generally short, blended gray fur. Largest range among wolf subspecies. Most common wolf subspecies in Europe and Asia. Population roughly 100,000. Hunted legally in some places, protected in others. |

| Great Plains Wolf |

Canis lupus nubilus |

Stable |

Southern Rocky Mountains, Midwestern United States, Eastern and Northeastern Canada, far Southwestern Canada, and Southeastern Alaska |

| An average-sized subspecies. Usually gray, black, buff, or reddish. The most common subspecies in the contiguous U.S. Hunted legally in parts of Canada. |

| Italian Wolf |

Canis lupus italicus |

Endangered |

Italy, Switzerland, France |

| An average-sized subspecies. Full canine color spectrum represented. Occupy comparatively smaller territories. Protected. |

| Mackenzie Valley Wolf |

Canis lupus occidentalis |

Stable |

Alaska, Northern Rockies, Western and Central Canada |

| A very large subspecies. Usually black or a blended gray or brown, but full color spectrum represented. This subspecies was reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho starting in 1995. Hunted legally in Alaska and parts of Canada. Protected in the contiguous states. |

| Mexican Wolf |

Canis lupus baileyi |

Critically endangered |

Central Mexico, Western Texas, Southern New Mexico and Arizona |

| A smaller subspecies. Usually tawny brown or rusty in color. Reintroduced to Arizona starting in 1998. Current wild population 35–50. Current captive population 300. Protected. |

| Russian Wolf |

Canis lupus communis |

Stable, declining |

Central Russia |

| A very large subspecies. Hunted legally. |

| Southern-East Asian Wolf |

Canis lupus pallipes |

Stable |

Northern Israel, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Afghanistan, Iran |

| A small subspecies. Hunted legally in some places, protected in others. |

| Tundra Wolf |

Canis lupus albus |

Stable |

Northern Russia, Siberia |

| A larger subspecies. Typically gray, with mixes of black, rust and silver, though full spectrum is represented. Hunted legally. |

| Vancouver Island Wolf |

Canis lupus crassodon |

Endangered |

Vancouver Island |

| Vancouver Island wolves are medium-sized and often gray. |

[edit] Disputed subspecies

Historically, gray wolf classification has been transient in nature. As a result, there still exists some disagreement as to the status of certain possible subspecies. These are listed below.

| Subspecies |

Classification |

Status |

Historic Range |

| Iberian Wolf |

Canis lupus signatus |

Stable |

North Portugal, North-Western Spain |

| May also be part of C. l. lupus. An average-sized subspecies. Distinct for its black markings and rusty red pelage. Conservation dependant. |

[edit] Former subspecies

[edit] Extinct subspecies

| Subspecies |

Classification |

Status |

Historic Range |

| Hokkaido Wolf |

Canis lupus hattai |

Extinct |

Japanese island of Hokkaidō |

| A smaller subspecies. Became extinct in 1889 as a result of poisoning campaigns. |

| Honshu Wolf |

Canis lupus hodophilax |

Extinct |

Japanese islands of Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū |

| A very small subspecies. Became extinct in 1905 from a combination of rabies and human eradication efforts. |

| Newfoundland Wolf |

Canis lupus beothucus |

Extinct |

Newfoundland, Canada |

| Became extinct in 1911 from a combination of human eradication efforts and a population decline in major prey species. |

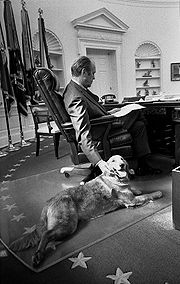

[edit] Relation to the dog

Much debate has centered on the relationship between the wolf and the domestic dog, though most authorities see the wolf as the dog's direct ancestor. Because the canids have evolved recently and different canids interbreed readily, untangling the relationships has been difficult. But molecular systematics now indicate very strongly that domestic dogs and wolves are closely related, and the domestic dog is now normally classified as a subspecies of the wolf: Canis lupus familiaris. The main differences between wolves and domestic dogs are that wolves have, on average, 20% larger brains, better immune systems, a better sense of smell, and are generally larger than domestic dogs.[46]

North American domestic dogs are believed to have originated from Old World wolves. No known dog breed is indigenous to America. The first people to colonize North America 12,000 to 14,000 years ago brought their dogs with them from Asia, and apparently did not separately domesticate the wolves they found in the New World.[47]

[edit] Interspecific predatory relationships

One of the most well researched wolf/predator interactions is that involving the coyote. Wolves are generally intolerant of coyotes in their territory, seeing them as competitors for food and as threats to their cubs; two years after their re-introduction to the Yellowstone National Park, the wolves were responsible for a near 50% drop in coyote populations through both competition and predation. Though smaller in size, coyotes are usually swift enough to escape the jaws of wolves and on some occasions, have even been known to gang up on them.[48] Near identical interactions have been observed in Greece between wolves and golden jackals.[49]

The cougar is another predator encountered by the gray wolf in North America. As with the coyote, the gray wolf is usually hostile toward the big cats and will kill cougar kittens if given the opportunity. The wolf's relation to adult cougars is more complex. A pack often takes advantage of cougars, stealing kills and sometimes killing mature adults. Interactions between solitary wolves and cougars are rarer, but the two species have killed each other.[50] National Park Service cougar specialist Kerry Murphy stated that the cougar usually is at an advantage on a one to one basis, considering it can effectively use its claws, as well as its teeth, unlike the wolf which relies solely on its teeth. Yellowstone officials have reported that attacks between cougars and wolves are not uncommon. Multiple incidents of cougars taking wolves and vice versa have been recorded in Yellowstone National Park. However, researchers in Montana have found that wolves regularly kill cougars in the area, though they did not specify whether or not this was a pack situation.[51]

Reconstruction of a wolf pack confronting a

Grizzly bear by Adolph Murie (1944)

Brown bears are among the few competitors wolves encounter in both Eurasia and North America, while the American black bear is encountered solely in the Americas. The majority of interactions between wolves and bears usually amount to nothing more than mutual avoidance. Serious confrontations depend on a variety of variables, though the most common factor is defence of food and young. Bears will use their superior size to intimidate wolves from their kills and when sufficiently hungry, will raid wolf dens. Wolves in turn have been observed killing bear cubs, to the extent of even driving off the defending mother bears. Deaths in wolf/bear skirmishes are however considered very rare occurrences, the individual power of the bear and the collective strength of the wolf pack usually being sufficient deterrents to both sides.[52]

In the Russian Far East, the gray wolf's status as an apex predator is challenged by the Siberian tiger. Siberian tigers have been known to prey on wolves and the two species compete for the limited prey base.[53] Studies have shown that gray wolf populations generally decrease in areas inhabited by the Siberian Tiger.[54]

In some Middle Eastern countries, the gray wolf will sometimes encounter the striped hyena, mostly in disputes over carcasses. Though not as powerful individually, the gray wolf's social nature usually puts the more solitary hyena at a disadvantage in confrontations.[55]

[edit] Historical perceptions

-

[edit] In folklore and mythology

-

For more details on this topic, see Werewolf.

Odin watching Tyr feed Fenrir

Traditionally humans held a distasteful view of wolves, a creature they feared. It was also often accentuated in European folklore beginning in the Christian era. Settlers brought this view with them as they settled North America. The gray wolf, once found in every ecosystem across the Northern Hemisphere, was one of the first species to be culled by settlers. As technology made the killing of wolves and predators easier, humans began to overhunt wolves and cause their numbers to dwindle significantly.

In Norse mythology, Fenrir or Fenrisulfr is a gigantic wolf, the son of Loki and the giantess Angrboða. Fenrir is bound by the gods, but is ultimately destined to grow too large for his bonds and devour Odin during the course of Ragnarök. At that time he will have grown so large that his upper jaw touches the sky while his lower touches the earth when he gapes. He will be slain by Odin's son, Viðarr, who will either stab him in the heart or rip his jaws asunder according to different accounts. Stories of werewolves can be found in virtually all European countries; these date back from Ancient Greek legend of Lycaon, who in one story was transformed into a wolf as a result of eating human flesh, and the writings of the Roman scholar, Pliny the Elder.[56]

Wolves are nevertheless portrayed positively in some myths and legends, and many languages have names meaning "wolf". Some examples include, for instance: Scandinavian Ulf, Albanian "Ujk", Hebrew Ze'ev, Hungarian Farkas, Serbian Vuk, and Bulgarian Vǎlko. Another sympathetic legend was the suckling of Romulus and Remus in the foundation of Rome.

In Japan, grain farmers once worshiped wolves at shrines and left food offerings near their dens, beseeching them to protect their crops from wild boars and deer. Talismans and charms adorned with images of wolves protected against fire, disease, and other calamities and brought fertility to agrarian communities and to couples hoping to have children. The Ainu people believed that they were born from the union of a wolflike creature and a goddess.[57]

In Altaic mythology of the Central Asian Turkic and Mongolian peoples, the wolf is a revered animal. The shamanic Turkic peoples even believed they were descendants of wolves in Turkic legends. The legend of Asena is an old Turkic myth that tells of how the Turkic people were created. In Northern China a small Turkic village was raided by Chinese soldiers, but one small baby was left behind. An old she-wolf with a sky-blue mane named Asena found the baby and nursed him, then the she-wolf gave birth to half wolf, half human cubs therefore the Turkic people were born. Also in Turkic mythology it is believed that a gray wolf showed the Turks the way out of their legendary homeland Ergenekon, which allowed them to spread and conquer their neighbours.[58][59] The genesis story of the Turks and Mongols is paralleled in the Roman myth of Romulus and Remus, the traditional founders of Rome. The twin babies were ordered to be killed by their great uncle Amulius, though the servant ordered to kill them however, relented and placed the two on the banks of the Tiber river. The river, which was in flood, rose and gently carried the cradle and the twins downstream, where under the protection of the river deity Tiberinus, they would be adopted by a she-wolf known as Lupa in Latin, an animal sacred to Mars.

More familiar still are the fairy tales where the wolf appears as a villain such as in Grimm's Fairy Tales, as well as the Aesopian Fable The Boy Who Cried Wolf.

[edit] Current status

Historically, the fear of wolves has been responsible for most of the species' trouble, including its near extinction in Europe and the United States during the 20th century. Ecological research in the 20th century has shed new light on wolves and other predators, specifically with regard to their critical role in maintaining ecosystems to which they belong. This information has led to a more positive portrayal in some countries.

A general increase in environmental awareness began to take root sometime in the middle of the 20th century and forced people to rethink former notions, including those regarding predators. In North America people realized that in over one hundred years of documentation, there had been no verified human fatalities caused by an attack from a healthy wolf.[60][61] Wolves are actually naturally cautious and will almost always flee from humans, perhaps only carefully approaching a person out of curiosity. There are, however, some reports of possible wolf attacks in North America that people assumed happen on a regular basis.[62] Although attitudes have significantly changed, there are still many who hold negative views of the wolf. In fact, there are many Americans who believe that the criteria a wolf attack has to fill (in order to be labeled as an actual attack) are unreasonable.

China apparently considers wolves as a "catastrophe" and claims that they live in only twenty percent of their former habitat in the northern regions of the country.[63] In 2006, the Chinese government began plans to auction licences for foreigners to hunt wild animals, including endangered species such as wolves. The licence to shoot a wolf can apparently be acquired for $200.[64]

[edit] Norway

In Norway, in 2001, the Norwegian Government authorised a controversial wolf cull on the grounds that the animals were overpopulating and were responsible for the killing of more than 600 sheep in 2000. The Norwegian authorities, whose original plans to kill 20 wolves were scaled down amid public outcry.[65] In 2005, the Norwegian government proposed another cull, with the intent of exterminating 25% of Norway's wolf population. A recent study of the wider Scandinavian wolf population concluded there were 120 individuals at the most, causing great concern on the genetic health of the population.[66]

[edit] Finland

Wolves cross over the border from Russia into Finland on a regular basis. Although they're protected under EU law, Finland has issued hunting permits on a preventative basis in the past, which resulted in the European Commission taking legal action in 2005. In June 2007 the European Court of Justice ruled that Finland had breached the Habitats Directive but that both sides had failed in at least one of their claims.[67] Finland's wolf population is estimated at around 250.[67]

[edit] Belarus

The northern and central regions of Belarus are home to perhaps 1,500 to 1,800 wolves. With the exception of specimens in nature reserves, wolves in Belarus are largely unprotected. They are designated a game species, and bounties ranging between €60 and €70 are paid to hunters for each wolf killed. This is a considerable sum in a country where the average monthly wage is €230.[68]

[edit] Romania

Romania has no direct livestock depredation control, however, if complaints about losses get too high, the holder of the hunting rights for the area might apply to kill a higher number of wolves during the winter hunting season. Poaching of carnivores occurs to some degree by means of traps, snares, or poison. The CLCP (Carpathian Large Carnivore Project) has initiated the use of electric fences as an additional tool for overnight livestock protection. The first tests have been very encouraging, with no losses of livestock at all.[69]

[edit] Slovakia

In Slovakia the 1994 Law on Protection of Nature and Landscape gave wolves full protection, though there is an annual two-month open season between 1st November to 15th January.[70]

[edit] Lithuania

The current size of the Lithuanian wolf population is said to be composed of 400-500 individuals.[71]

[edit] Bulgaria

Bulgaria considers the wolf a pest and there's a bounty equivalent to two week's average wages on their heads. [72]. A project run by the Balkani Wildlife Centre aims to reduce conflict between farmers and wolves by supplying Livestock guarding dogs as well as by educating the locals about large carnivores and their role in nature.

[edit] Croatia

According to estimates of experts from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Zagreb, there are 130 to 170 wolves in Croatia and their population is presently stable.[73]. Attitudes are changing in favour of wolves and the animals are now protected under Croatian law [74]. Furthermore, there have been cases of villagers reporting injured wolves to biologists rather than simply killing them. [74]

[edit] Ukraine

Though wolf populations have increased in Ukraine, wolves remain unprotected there and can be hunted year-round by permit-holders.[70]

[edit] Russia

In Russia, government backed wolf exterminations have been largely discontinued since the fall of the Soviet Union. As a result, their numbers have stabilized somewhat, though they are still hunted legally. It is estimated that nearly 15,000 of Russia's wolves are killed annually for the fur trade and because of human conflict and persecution. Due to the new capitalist government's focus on economy, and other issues plaguing the former communist nation, the study of wolves has been largely discontinued from lack of funding.[75]

[edit] Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is currently thought to have the largest wolf population of any nation in the world, with as many as 90,000, versus some 60,000 for Canada, which is three and a half times larger. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, wolf hunting has decreased in profit. About 2,000 are killed yearly for a $40 bounty, and the animal’s numbers have risen sharply. At the same time, poachers have reduced the Kazakhstani wolf’s main prey species, the saiga antelope, from 1.5 million to perhaps 150,000, selling horns to the Chinese, who use it in traditional medicine. The great number of saiga accounted for the large number of wolves in Kazakhstan. Now, after the antelope’s decline wolves encroach upon human habitations in the Winter periods and attack livestock. In the spring, they go back to the remote, lightly wooded Amangeldy Hills to reproduce and feed on small mammals.[3]

There are currently no protection laws in Egypt, and the last estimate was that there remain only 30-50 Egyptian Wolves still in existence. [1]

Starting from the 1970s, political debates began favouring the increase in wolf populations. A new investigation began in the early 1980s, in which it was estimated that there were now approximately 220-240 animals and growing. New estimates in the 1990s revealed that the wolf populations had doubled, with some specimens taking residence in the Alps, a region not inhabited by wolves for nearly a century. Current estimates indicate that there are 500-600 Italian wolves living in the wild. Their populations are said to be growing at a rate of 7% annually.[76]

[edit] France

Wolves migrated from Italy to France as recently as 1992. The French wolf population is still no more than 40-50 strong, but the animals have been blamed for the deaths of nearly 2,200 sheep in 2003, up from fewer than 200 in 1994. Controversy also arose when in 2001, a shepherd living on the edge of the Mercantour National Park survived a mauling by three wolves.[77] Under the Berne Convention wolves are listed as an endangered species and killing them is illegal. Official culls are permitted to protect farm animals so long as there is no threat to the species.[78]

[edit] Germany

Around 35 wolves in 4 packs are now roaming the heaths of the eastern German region of Lusatia, a region along the German-Polish border, and they are now still expanding their range to the west and the north.[79] Wolves were first spotted in the area back in 1998, and are thought to have migrated from western Poland.[80] On December 15, 2007, a male wolf has been shot illegally in the district of Lüchow-Dannenberg, Lower Saxony.[81]

[edit] Poland

It is thought that there are around 500 to 600 wolves in Poland, mainly in the east.

[edit] Attacks on humans

-

[edit] Causes and prey selection

Wolf devouring woman, 18th century print

Although wolves very rarely attack humans, the causes of wolf attacks may vary greatly. Habitat loss for example can cause the wolf's natural prey to diminish and thus cause the local wolves to turn to attacking livestock or on some rare occasions, even people. Close proximity to humans may also cause habituation. In this case, wolves lose their fear of humans and consequently approach too close. Habituation usually happens when people encourage wolves to come up to them, usually by offering them food, or when people do not sufficiently intimidate wolves. Habituation can also occur accidentally. With unrestricted hunting, forest clearing and intensive livestock grazing there is little natural prey, therefore forcing the wolves to feed on domestic animals and garbage, thus bringing them in close proximity to humans. However, wild wolves are often timid around humans, and usually try to avoid contact with them, to the point of even abandoning their kills when an approaching human is detected.[82]

A recent Fennoscandian study on historical wolf attacks occurring in the 18th–19th centuries indicated that victims were almost entirely children under the age of 12, with 85% of the attacks occurring when an adult was not present. In the few cases when an adult was killed, it was almost always a woman. In nearly all cases, only a single victim was injured in each attack, although the victim was with 2–3 other people in a few cases. This contrasts dramatically with the pattern seen in attacks by rabid wolves, where up to 40 people could be bitten in the same attack. It should also be noted that some recorded attacks occurred over a period of months or even years. This makes the likelihood of rabies infected perpetrators unlikely, considering that death usually occurs within 2–10 days after the initial symptoms. The attacks tended to be clustered in space and time. This indicates that human- killing was not a normal behaviour for the average wolf, but was rather a specialised behaviour that single wolves or packs developed and maintained until they were killed.[83]

Rabies can account for attacks made by lone wolves, though it is unlikely if the perpetrators function as a pack, seeing as rabid wolves are loners.[84]

Though wolf attacks in North America are very rare, they do occur somewhat more frequently in the Old World, usually occurring in rural, poverty stricken areas where the people have no firearms or other effective means of predator control.

[edit] North America

Though most Native American tribes revered wolves, their oral history does confirm that they were in fact on occasion attacked by wolves long before the arrival of European settlers. Woodland Indians were usually the most at risk, as they would often encounter wolves suddenly and at close quarters. An old Nunamiut hunter once said in an interview with author Barry Lopez that wolves used to attack his people, until the introduction of firearms, at which point the attacks ceased.[16]

When settlers began colonizing the continent, they noticed that though the local wolves were more numerous than those in Europe, they were less aggressive.[16] In Canada, an Ontario newspaper offered a $100 reward for proof of an unprovoked wolf attack on a human. The money was left uncollected.[85] Though Theodore Roosevelt considered the large timber wolves of north-western Montana and Washington to be equal in size and strength to Northern European wolves, he noted that they were nonetheless much shyer around man.[86]

In modern times, as humans begin to encroach on wolf habitat more contacts are being noted. Often the contact is because the person is walking their pet dog and the wolf pack considers the dog a prey item, inciting an attack.[87][88][89][90]

[edit] Europe

In Scotland, during the reign of James VI, wolves were considered such a threat to travellers that special houses called "spittals" were erected on the highways for protection.[85] The people of the Scottish Highlands used to bury their dead on offshore islands to avoid having the bodies eaten by wolves.[91] In Imperial Russia 1890, a document was produced stating that 161 people had been killed by wolves in 1871.[85] During the First World War, starving wolves had amassed in great numbers in Kovno and began attacking Imperial Russian and Imperial German fighting forces, causing the two fighting armies to form a temporary truce to fight off the animals.[92]

A hypothesis as to why wolves in Eurasia act more aggressively toward humans than those in North America is that in the past, Old World wolf hunting was mostly an activity for the nobility, whereas American wolf hunts were partaken by ordinary citizens, nearly all of them possessing firearms. This difference could have caused American wolves to be more fearful of humans, making them less willing to venture into settled areas.[84]

Nevertheless, with the exception of one attack on a French shepherd in 2001[93], modern Western Europe has had very few attacks and no recent fatalities. "Lupus," a German group of wildlife biologists says it has documented 250 encounters between people and wolves in the Lusatia region and there were no problems in any of the cases.[94]

[edit] Reintroduction

-

[edit] North America

In certain parts of the world, debate about wolf reintroduction is ongoing and often heated, both where reintroduction is being considered and where it has already occurred. Where wolves have been successfully reintroduced, as in the greater Yellowstone area and Idaho, reintroduction opponents continue to cite livestock predation, surplus killing, and economic hardships caused by wolves.[95] Opponents in prospective areas echo these same concerns.

Gray wolf endangered species sheet

However, what the Yellowstone and Idaho reintroductions demonstrate is how compromise can be used to satisfy relevant interests. These reintroductions were the culmination of over two decades of research and debate. Ultimately, the economic concerns of the local ranching industry, arguably the single best reason used against reintroduction, was dealt with when Defenders of Wildlife decided to establish a fund that would compensate ranchers for livestock lost to wolves, shifting the economic burden from industry to the wolf proponents themselves.[96] The majority of the organizations opposing reintroduction relented their "no wolf, no way" stance when this crucial deal breaker was resolved.

As of 2005, there are over 450 Mackenzie Valley wolves in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and over 1,000 in Idaho. Both populations have long since met their recovery goals and the reintroduction experiment has been a resounding success. Still, lessons learned from this ordeal may yet prove useful where wolf reintroduction continues to create a sharp divide between industry and environmental interests, as it has in Arizona (where the Mexican Wolf was released beginning in 1998). In some other Western and Central European countries, the debate will likely impair wolf reintroduction efforts where they are being considered, but, as history has validated, industry need not be ignored for a reintroduction effort to be successful.

Though many hunters, prior to and even after reintroduction, claimed that wolves would wipe out entire populations of elk, deer and other ungulates, most ecosystems where wolves have been reintroduced have actually become much healthier than they were before. Since Wolves have arrived, the food chain within the Yellowstone ecosystem has been re-ordered to deliver a banquet that favors a more varied array of species. Prior to wolves, high numbers of elk were linked to declines in aspen and willow communities, which negatively affected beaver and moose. Pre-wolf, coyote numbers swelled, affecting small rodent populations, foxes, and the production of pronghorn antelope. Pre-wolf scavengers had slimmer pickings. Today with wolves taking elk, reducing their numbers, and leaving more carcasses on the landscape, grizzlies and wolverines have easier access to more meat, meaning a better chance for larger litters of cubs and pups. Coyote numbers have been significantly reduced, meaning more mice and pocket gophers for foxes and avian predators like hawks and eagles.[97] Wolves play an undeniably important role in the environment and through education organizations some people may be slowly getting the message that they are vital. In addition, reports have been published placing the value of revenue from wolf-watching as upward of $25 million.

[edit] United Kingdom

The British Government signed conventions in the 1980's and 1990's, agreeing to consider reintroducing wolves and to promote public awareness about them. Being party to European conventions, the British government is obligated to study the desirability of reintroducing extinct species and to consider reintroducing wolves. Although there are indications that wolves are recolonizing areas in Western Europe, they are unable to return to their former ranges in Britain without active human assistance.

The Scottish Highlands are one of the few large areas in western Europe with a relatively tiny human population, thus ensuring that wolves would suffer little disturbance from human activity. One popular argument in favour of the reintroduction is that the Highland's red deer populations have overpopulated and a reintroduction of wolves would aid in keeping their numbers down, thus allowing the native flora some respite. Other arguments include the generation of income and local employment in the Highlands through wolf ecotourism which could replace the declining and uneconomical Highland sheep industry.[98]

[edit] Wolf hunting

-

Main article: Wolf hunting

[edit] Livestock predation

Wolf sneaking to the sheepfold past a sleeping shepherd, Aberdeen Bestiary, 12th century

As long as there is enough prey, wolves seem to avoid taking livestock, often ignoring them entirely.[99] However, some wolves or packs can specialize in hunting livestock once the behavior is learned despite natural prey abundance. In such situations, sheep are usually the most vulnerable, but horses and cattle are also at risk. Wolf-secure fences, relocation where applicable and sometimes hunting wolves are the only known methods to effectively stop livestock predation.

Wolves have been known to commit acts of surplus killing when within the confines of human made livestock shelters. Rare incidents of surplus killing by wolves in Minnesota are reported to leave up to 35 sheep killed and injured in flocks and losses of 50 to 200 birds in turkey flocks.[41]

Large domestic animals such as cattle or yak are killed by biting at the shoulders and flanks. A trail of blood and patches of hair are often evident. Individual wolves and small packs sometimes concentrate on the flank and hind legs. The prey is often left to weaken, being fed upon once it falls. Wolf bites usually causes damage deep in the underlying tissues. Cattle severely injured by wolves often appear dazed and are reluctant to move due to the deep pain. Wolves usually feed on cattle at the kill site, with parts sometimes being carried off. Wolves prefer to feed on the viscera and hind legs of domestic prey, though bones are often chewed and broken.[100]

Wolves usually disregard size or age on medium sized prey such as sheep and goats. Injuries may include a crushed skull, severed spine, disembowelment and massive tissue damage. Wolves will also kill sheep by attacking the throat, similar to the manner in which a coyote kills sheep. Wolf kills however, can be distinguished by the fact that they damage the underlying tissue much more. Surplus killing often occurs.[100]

Over several centuries, shepherds and dog breeders have used selective breeding to "create" large livestock-guarding dogs that can stand up to wolves preying on flocks.[101] In the U.S., in light of the gray wolf and other large predators having recently been reintroduced to certain areas, the United States Department of Agriculture has been looking into the use of breeds such as the Akbash from Turkey, the Maremma from Italy, the Great Pyrenees from France, and the Kuvasz from Hungary, among others, to help limit wolf-livestock interactions. Wolves however have been known to kill dogs. It has been theorized that wolves view dogs as competitors, which explains why the majority of attacked pets are usually hunting dogs unwittingly entering the wolf's turf.[102] In some instances, wolves have displayed an uncharacteristic fearlessness of humans and buildings when attacking dogs, to an extent where they have to be beaten off or killed.[103] Few dogs can hold their own against lone wolves, let alone wolf packs. Notable exceptions include specially bred Livestock guardian dogs, though their primary function has more to do with intimidating the wolves rather than fighting them.[104] Conversely, wolves have on occasion been known to mate with dogs to produce mix-breed offspring known as wolfdogs. Although there has been concern that European wolf populations may have extensively hybridized with stray dogs, truly significant genetic contamination of dog genes into wild wolf populations has not been confirmed. The extent of physical and behavioural differences between dogs and wolves is usually great enough to ensure that mating is unlikely and hybrid offspring rarely survive to reproduce in the wild.[105]

In some areas across the world, hunters or state officials will hunt wolves from helicopters or light planes to control populations (or for sport in some instances), citing it as the most effective way to control wolf numbers, given that traditional poisons are largely banned. The method is used where interactions between livestock and wolves are common, or where sport or subsistence hunters desire more game animals with less competition. Aerial hunting is seen as highly controversial. In areas where aerial hunting is used to limit livestock-wolf interactions or to boost populations of game animals, arguments against it are usually centered around whether or not the reasons behind such predator elimination are scientifically valid.

Other, non- or less-lethal methods of protecting livestock from wolves have been under development for the past decade. Such methods include rubber ammunition and use of guard animals.[106]

[edit] North America

While wolf predation on livestock does happen, loss of livestock by wolves makes up only a small percentage of total losses in North America. Since the state of Montana began recording livestock losses due to wolves back in 1987, only 1,200 sheep and cattle have been killed. 1,200 killings in twenty years is not very significant when in the greater Yellowstone region 8,300 cattle and 13,000 sheep die from natural causes. According to the International Wolf Center, a Minnesota-based organization:

To put depredation in perspective, in 1986 the wolf population was at about 1,300–1,400, there were an estimated 232,000 cattle and 16,000 sheep in Minnesota's wolf range. During that year 26 cattle, about 0.01% of the cattle available, and 13 sheep, around 0.08% of the sheep available, were verified as being killed by wolves. Similarly, in 1996 an estimated 68,000 households owned dogs in wolf range and only 10, approximately 0.00015% of the households, experienced wolf depredation.

– Wolf Depredation, International Wolf Center, Teaching the World about Wolves[107]

Furthermore, Jim Dutcher, a film maker who raised a captive wolf pack observed that wolves are very reluctant to try meat that they have not eaten or seen another wolf eat before possibly explaining why livestock depredation is unlikely except for in cases of desperation.[108]

[edit] Eurasia

The results however differ in some Old World countries. Greece for example reports that between April 1989 and June 1991, 21000 sheep and goats plus 2729 cattle were killed. In 1998 it was 5894 sheep and goats, 880 cattle and very few horses. [49] A study on livestock predation taken in Tibet showed that the wolf was the most prominent predator, accounting for 60% of the total livestock losses, followed by the snow leopard (38%) and lynx (2%). Goats were the most frequent victims (32%), followed by sheep (30%), yak (15%), and horses (13%). Wolves killed horses significantly more and goats less than would be expected from their relative abundance.[109] In 1987, Kazakhstan reported over 150,000 domestic livestock losses to wolves, with 200,000 being reported a year later.[29]

[edit] Trapping and breeding for fur

"How Wolves may be caught with a Snare," 15th century.

Wolves are frequently trapped, in the areas where it is legal, using snares or leg hold traps. Wolf trapping has come under heavy fire from animal rights groups, who allege that unskilled trappers can create unnecessary suffering for the animal involved.[110] Proponents counter that trapping, using the right tools and equipment, can be considered as humane as traditional hunting.[111]

Wolves are also bred for their fur in a very few locations, but they are considered as a rather problematic animal to breed, and, combined with the low value of the pelt, most fur farms utilize other animals. Wolves' varied coats make it difficult to create fur coats.

It is known that some Native American tribes would occasionally raise wolf pups for their fur. The pelt served as a shield against the cold and as an important addition to rituals.[16] Eskimoes tend to prefer dog skin over that of wolves, seeing as the latter is less resistant to wear and tear.[13]

Biologists may also trap wolves for research purposes. Darting and foot hold traps are the tools of choice for such professionals, who often use these and similar techniques to fit wolves and other animals with collars holding radio transmitters and to check their health before releasing them. Use of such technology also allows them to keep track of population numbers and dispersal trends, among other things. Radio collars can also be used to monitor wolves when they come near livestock, and to identify a wolf or a pack that preys on livestock, allowing proper action to be prompter and more accurate.

[edit] See also

Extinct Gray wolves:

Historical wolves

Other extant and extinct canid species also known as wolves:

Dog breeds with recent wolf ancestry:

[edit] Notes and references

- ^ Mech & Boitani (2004). Canis lupus. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. Retrieved on 2006-05-05. Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern.

- ^ Lindblad-Toh, K, et al. (2005). "Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog". Nature 438: 803–819.

- ^ a b Is Kazakhstan Home to the World’s Largest Wolf Population?. Christopher Pala. National Wildlife Federation. Retrieved on 2007-09-28.

- ^ a b Grey Wolves. Yellowstone-Bearman (November 2002). Retrieved on 2007-03-17.

- ^ Persecution and Hunting. Endangered Species Handbook. Animal Welfare Institute. Retrieved on 2006-08-20.

- ^ a b Wolf Facts. California Wolf Center. Retrieved on 2006-08-21.

- ^ Dog Family. Safari Club International Foundation. Retrieved on 2006-08-22.

- ^ Hodgson, Angie (July 1997). Wolf Restoration in the Adirondacks? (PDF). Wildlife Conservation Society. Retrieved on 2006-08-21.

- ^ Gray Wolf Biologue. Midwest Region. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved on 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Wolf". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth Edition). New York: Columbia University Press. Retrieved on 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Claws reveal wolf survival threat". Paul Rincon. BBC online. Retrieved on 2007-05-11.

- ^ a b c d Gray Wolf. Corwin's Carnival of Creatures. Animal Planet. Retrieved on 2006-05-24.

- ^ a b Coppinger, Ray (2001). Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution, p352. 0684855305.

- ^ Macdonald, David (1992). The Velvet Claw, 256. 0563208449.

- ^ Ellis, Shaun (2006). Le Loup : Sauvage et Fascinant, pp.225. ISBN 2749905389.

- ^ a b c d e f Lopez, Barry (1978). Of wolves and men, pp.320. ISBN 0743249364.

- ^ Wolf Pup Development. Wolf Basics. International Wolf Center (November 2004). Retrieved on 2006-08-23.

- ^ About Wolves. The Wolf Spirits. Retrieved on 2006-08-21.

- ^ Wolf. 4to40.com. Retrieved on 2006-08-22.

- ^ The skull of Canis lupus. World of the Wolf. Natural Worlds. Retrieved on 2005-08-21.

- ^ a b Mating system. Department of Biology, Davidson College. Retrieved on 2006-08-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dewey, Tanya (2002). Canis lupus. Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved on 2005-08-18.

- ^ Gray Wolf. Discover Life in America. Retrieved on 2005-05-05.

- ^ Wolves, Coyotes and Fox. MountainNature.com. Retrieved on 2006-08-23.

- ^ a b Wolfmovie.com Forum Index - Wild Wolves. Wolf Movie Forums. Retrieved on 2006-08-23.

- ^ a b c d Harper, Liz (November 2002). FAQ. Wolf Basics. International Wolf Center. Retrieved on 2005-08-21.

- ^ a b Gray Wolf Biology and Status. Wolf Basics (March 2005). Retrieved on 2006-08-23.

- ^ Huber, Đuro Huber; Josip Kusak, Alojzije Frković, Goran Gužvica. "Causes of wolf mortality in Croatia in the period 1986-2001" (PDF). Veterinarski Arhiv 72 (3): 131–139. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ^ a b Wolves in Russia. Will N. Graves. Retrieved on 2007-09-05.